By Daniel Butcher

The role of social class in the workplace is not as discussed as it should be, as it plays a big role in who earns promotions and raises—and who decision-makers include and listen to in meetings. The consequence is that many deserving professionals from lower social classes get unfairly passed over, while those who do get their due in moving up the ladder often outshine their more privileged peers.

Academy of Management Scholar Sean Martin of the University of Virginia explained that social-class backgrounds shape us almost like different cultures. A person who has been upwardly mobile through different social-class positions and professional ranks is akin to being multicultural.

“People who have been upwardly mobile have been shaped in very different ways than people who might have always been in fairly privileged positions, in ways that make them have to learn new cultural norms and reach across cultural divides, as they’ve had to do as they move into new and higher social-class settings,” Martin said. “They come equipped with a skill set, including communication skills, and experiences that are very useful.

“My own research finds that people who come from lower social-class backgrounds who’ve been upwardly mobile are actually quite likely to speak up and offer a fresh perspective,” he said. “The real challenge is that bosses often don’t ask them for their input as often as they would ask it from people who come from more privileged backgrounds.”

People who come from a more elite background typically have many indicators of being from an upper social class, for example, having gone to prestigious schools, saying urbane things that are very culturally savvy in a particular accent that makes them sound smart, and an expensive mode of dressing that is taken for granted in that echelon. And all of those qualities make an impression on supervisors.

“Upper-class people may have that ‘it’ factor—they went to name-brand schools, have name-brand clothes, and say these things that sounds so smart, so bosses say, ‘I’m going to go to them for their input,’ as opposed to a person who might speak more plainly, making the same point but in a very different way, or might have gone to an extremely good school, but maybe not a brand that jumps off the page at you,” Martin said.

“There have been really interesting studies that showed there’s actually a class ceiling and a class pay gap, just like there’s a gender ceiling and a gender pay gap, such that people working the same position who are from a lower social-class background essentially get paid less than a person who’s doing the same job but comes from an upper-class background, so coming from a lower-class background is inhibiting in those ways as well,” he said.

“A lot of my research tries to flip the script and say, ‘Let’s focus on all those multicultural abilities and all the ways that people have been shaped on that upwardly mobile journey that are incredibly useful and valuable, especially pertaining to leadership.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

When Entrepreneurs Can’t Acknowledge Failure, Disaster Strikes

By Daniel Butcher

Elizabeth Holmes, who was convicted of fraud for lying about the effectiveness of the blood-testing product of her biotechnology company, Theranos, is a cautionary tale illustrating a potential downside of entrepreneurship. Unable to deal with the failure of her company’s blood-testing methods, she just plowed ahead, refusing to acknowledge the disappointing results or telling any of the investors—or anyone else—that the tests weren’t working. She pretended like everything was okay, continued to collect investor money, and built up the biotech startup to a $9 billion valuation.

Academy of Management Scholar Dean Shepherd of the University of Notre Dame said that it’s common for entrepreneurs to deal with failure poorly, but investors failed to effectively scrutinize Theranos.

“A lot of the stakeholders there were maybe willfully ignorant—they wanted to believe her,” Shepherd said. “They didn’t ask probing questions; they ignored the negative signals, which is what we call a confirmation device.

“They look for information that confirms their opinions, and they discount or ignore information that disconfirms them, and so in many ways, she was negligent, but they were also negligent,” he said.

Sometimes entrepreneurs can’t even acknowledge failure to themselves, much less publicly, because their entire identity is wrapped up in success. One major failure could crack that self-image.

Shepherd said that job loss—or the failure of one’s business—can devastate a person’s sense of identity. He wrote about his research findings related to such phenomena in Hitting Rock Bottom After Job Loss: Bouncing Back to Create a New Positive Work Identity.

“Failure can have a huge impact on you psychologically, because your identity is quite often highly related to the things that you do for work, and when you lose that identity, you go into a crisis or a freefall, because you don’t know who you are anymore,” Shepherd said. “And if you don’t know who you are, you don’t know how to socially act, and it can be a very dangerous situation.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

Entrepreneurial Success Requires Luck as Well as Hard Work

By Daniel Butcher

There’s a dirty little secret about what separates successful entrepreneurs from those who fail: Many of the winners have luck on their side, and many of the failures work just as hard but don’t succeed through no fault of their own, according to Academy of Management Scholar Dean Shepherd of the University of Notre Dame.

Shepherd said that stories of entrepreneurs who have failed quite a bit are common. There’s often a disconnect between how investors and other entrepreneurs view them and how they are portrayed in the media.

“You sometimes see it in Silicon Valley, where they say, ‘I’ll only invest in in entrepreneurs who have failed before, because it means that they’ve learned and they know to make tough decisions,’ whereas you see press reports in other parts of the world, or even other parts of America, where they really penalize an entrepreneur who’s failed, despite the fact that they tried their best,” Shepherd said.

“They lost their own wealth, but the media ridicule people who have failed,” he said. “I see that in the press sometimes, where they attribute success to the person’s skills and experience, but then when someone fails, they say that there’s something fundamentally wrong with that person, and the press has an anti-failure bias, which doesn’t help.”

Luck be a lady

Unsuccessful entrepreneurs may have had to deal with a challenging external environment or competitive landscape or face any number of variables beyond their control—regardless of their skills, experience, and effort.

“They could have done everything right and then had bad luck, and the other person could have done everything wrong, and just by luck, they ended up being in the right place at the right time, and they were successful,” Shepherd said. “In either case, you don’t actually learn much from those instances, because luck played such a large role, but then they’ll attribute the person who was successful to their decisions and actions, even though it wasn’t the case, and they’ll attribute failure to the person’s decisions and actions, but it wasn’t the case.

“And so it’s really like a form of superstitious learning,” he said. “We’re learning something, but actually not gaining any knowledge from it. We’re learning something that’s wrong.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

People Use Crowdfunding to Show Compassion

By Daniel Butcher

The nonfinancial support that crowdfunding platforms such as GoFundMe provide via social media is crucial for raising awareness about charitable causes, entrepreneurial initiatives, and people who need help. For example, dozens of GoFundMe campaigns sprung up in the wake of a mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, on Valentine’s Day 2018.

Academy of Management Scholar Dean Shepherd of the University of Notre Dame said that crowdfunding has given the world a new way to help people whose lives have been upended by disasters and tragedies.

“Another part of crowdfunding in addition to raising money was more like a social movement focused on how we prevent these things from happening again in the future,” Shepherd said.

“So in some ways, the platform provides a basis for which communities can come together and display compassion, by which we mean trying to alleviate the suffering of other people, but perhaps also create these social movements to try and change the legislation, trying to change laws to try and improve life for people,” he said.

Hundreds of millions of people have donated more than $30 billion for mostly charitable causes through GoFundMe since it launched in 2010. Budding and would-be entrepreneurs have long used the platform to try to get funding for their business ideas, but using it in such as multifaceted way to process a tragedy was rare at the time of the Parkland shooting in 2018.

“It’s a unique way of using this crowdfunding,” Shepherd said. “It was an emotional outpouring of compassion for people shattered by a crisis demonstrating that crowdfunding can also be used for that purpose in addition to trying to fund new products and new services as well—that’s interesting.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

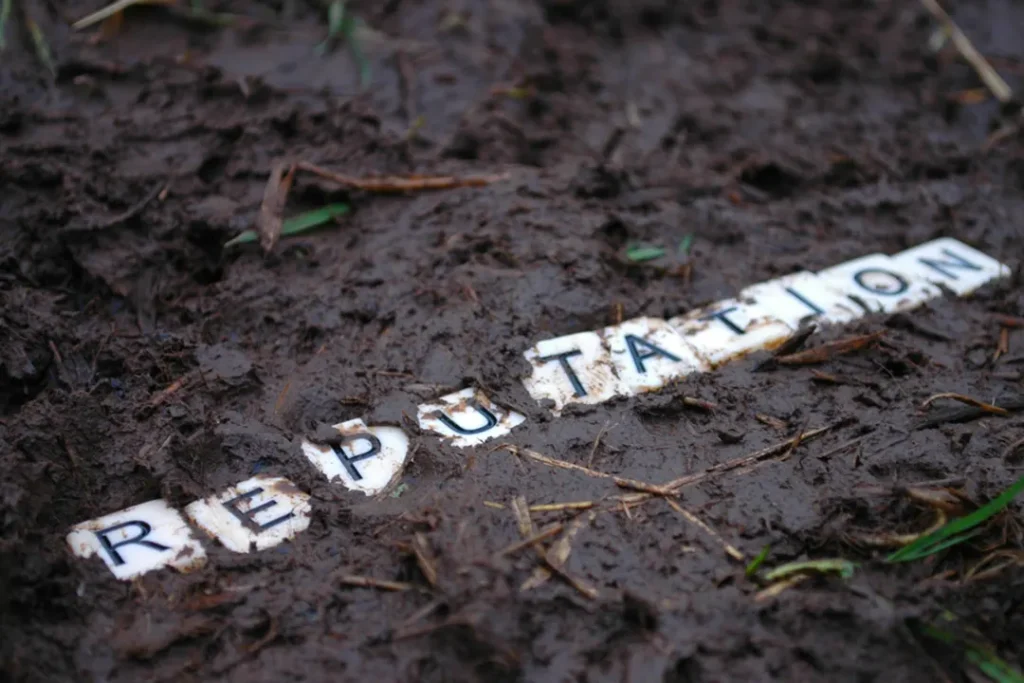

Media Magnify Scandals of Big-Name Companies

By Daniel Butcher

Companies that dominate their industries also have to deal with increased scrutiny. Any negative news, from layoffs and unethical conduct to data breaches, get amplified and can easily become scandals, according to Academy of Management Scholar Tim Pollock of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Media attention is drawn by the accused or guilty party’s prestige, he said.

“If the perpetrator is high-reputation, they may get the benefit of the doubt for less severe misconduct as some kind of one-off thing, and the media may be less likely to cover it,” Pollock said. “But if the misconduct is severe, then the media is even more likely to scandalize the high-reputation firm’s misconduct, because we don’t expect that from high-reputation firms; it violates our expectations.

“When we have high expectations about a firm’s behavior, whether because we expect them to be more competent or act with more integrity, it’s a bigger deal and more disturbing when they violate that expectation,” he said. “That makes the incident more newsworthy to the media, increasing their coverage of the misconduct.

“These are sorts of things that we’re looking at and trying to understand: What are misconduct aspects and firm characteristics lead the misconduct to become a scandal?”

Pollock and colleagues compared the reactions to data breaches at two different companies of vastly different levels of prestige and name recognition: Facebook and Chegg, a U.S. education technology company that provides homework help, textbooks, online tutoring, and other student services.

“Facebook had a data breach of 50 million accounts; it was covered widely in the media and got lots of attention—thousands of articles were written about their data breach and the problems with it,” Pollock said. “And literally on the same day, Chegg, which is an academic software company, had a similar data breach—40 million accounts were breached, but it was barely covered outside of the the specialist media on data security, and a little bit in the in the education sector.

“So why Facebook and not Chegg? Facebook is better known,” he said. “More people use Facebook and have given them their data, so the expectancy violation is greater and possibly more personal.

“Journalists recognize this, and thus are more likely to scandalize the incident, because it attracts more readers.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

The Disconnect Between Leaders and Patients on Healthcare

By Daniel Butcher

Many people hurt by the high costs and insurance denials plaguing the U.S. healthcare industry might have been hoping that the response to the December 2024 killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson would lead to reforms. However, most industry executives have tried to go back to business as usual, except with heightened security for senior executives, according to Academy of Management Scholar Tim Pollock of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

In response to the waves of criticism directed at U.S. health insurance and benefits-administration executives in the wake of Thompson’s killing, most industry leaders followed a typical crisis-management playbook, including a predictable public-relations script, he said.

“They’ve been saying all the things that they always say: that they’re beholden to achieving financial goals and medical providers’ increasing costs—‘medical costs go up, and so the insurance premiums have to go up’—and that they’re doing their best to provide coverage, and all these sorts of things, the usual platitudes that they roll out,” Pollock said. “But in terms of actually making some substantive changes, they don’t do much.”

“We’re one of the only countries in the world where healthcare coverage is privatized, and we’ve got the most expensive healthcare in the world with the 44th-best health outcomes,” he said. “It’s hard to justify the status quo on any rational basis.

“So if they want to repair and protect their reputation with customers and avoid this kind of backlash in the future, they have to understand where the customer is coming from and then find ways to speak to those problems and offer up a set of policies or practices they’re going to engage in—changes they’re going to make—to make this easier and better for customers.”

Health industry executives who try to defend the status quo of the U.S. healthcare system come off as tone-deaf at best, and uncaring or willfully dismissive of people’s suffering at worst.

“One of the mistakes that a lot of CEOs make is they try to defend the status quo, instead of saying, ‘You’re right; we’re not doing what we should be doing,’ and then, ‘Here’s what we’re going to do to make it to make it better,’” Pollock said. “There’s a whole other set of issues related to whether or not these things get implemented, but at least symbolically acknowledging their pain, their anger, taking some responsibility for it, and then saying, ‘We’re going to make changes that will address these problems and make things better going forward’ counts for something.

“But if they come out and talk about profitability, that their responsibility is to shareholders, or that this isn’t really a problem, or try to downplay the challenges that people have with high costs, denials of coverage, and administrative burdens, there’s a disconnect from patients’ experiences,” he said. “This is the issue you run into when leaders and customers are coming at a problem from opposite sides or completely different perspectives.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

Why Many Leaders Ignore Criticism

By Daniel Butcher

In the wake of the U.S. public’s reaction to the killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson and the arrest of suspect Luigi Mangione, some CEOs in the health insurance industry downplayed the tragedy, rather than thinking about the root cause of people’s anger directed toward them.

Keeping blinders on is a red flag for narcissism, according to Academy of Management Scholar Tim Pollock of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. He and Arijit Chatterjee of ESSEC Business School researched narcissistic CEOs and found that the more narcissistic the executives are, the more likely they are to ignore critical messages, and surround themselves with yes-men.

“Many CEOs, especially narcissistic ones, surround themselves with people who say, ‘No, don’t listen to the critics. You’re great. You’ve done nothing wrong. Everything’s wonderful,’ as opposed to saying, ‘Hey, we’ve got a real problem that we need to fundamentally think through and deal with,” Pollock said. “So there’s nobody to rein in CEOs when they’re making bad decisions or alert them to a blind spot that they have.

“We all have good ideas and bad ideas, but leaders need people to tell them when they have a bad idea and to stop them from from acting on it,” he said. “When you don’t have those people in place telling the CEO to tap the brakes, the bad ideas just spread, and a narcissistic CEO doesn’t want to hear the negative stuff, whereas a less narcissistic CEO who really wants todo the best job possible will actually cultivate that and make sure they have people around them who will tell them the truth, even if it’s something that they don’t really want to hear, but that they need to hear.

“But a narcissistic CEO will fire truthsayers; they’ll get rid of people who they perceive as disloyal for telling them negative stuff or telling them that they’re wrong.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

Reactions to CEO’s Killing Illustrate U.S. Health Insurers’ Bad Rep

By Daniel Butcher

The killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson in New York in December 2024 exposed Americans’ intense frustration and deep-seated anger at the U.S. healthcare system. They’re forced to pay more and more for health insurance every year, while dealing with administrative burdens and denials of doctor-recommended procedures, medications, and other medical services.

Academy of Management Scholar Tim Pollock of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville said that people’s reactions to Thompson’s killing point to the horrible reputation that the U.S. health insurance industry has with the general public.

“Almost anyone in the U.S. you talk to about health insurance has complaints—I’m sure you could probably recount your own healthcare or health insurance war story, when something got declined, or you had problems getting treatment or getting [a procedure or medication] paid for,” Pollock said. “It happens to everybody in the U.S., and in some cases it can be pretty devastating, resulting in bankruptcy and losing all your assets when you have to absorb the costs when coverage is denied for a medical emergency or an expensive medical treatment.

“So there’s a lot of anger around how our healthcare system has been working or failing to work for for people, and it creates this pent-up anger in the [American] populace,” he said. “And so, aside from leading one person who was clearly having additional issues to go out and kill the CEO of UnitedHealthcare, you see the public respond by putting up these social-media posts, like ‘Request for thoughts and prayers denied’ and ‘You failed to get prior approval for having an object removed from your chest, so therefore, it will not be covered’—that kind of stuff, and making the shooter almost a folk hero in certain quarters.

“These kinds of posts that people are putting out there and many others cheering them on speaks to the anger that folks have.”

Merriam-Webster defines infamy as an “evil reputation brought about by something grossly criminal, shocking, or brutal.” Some health insurance leaders have looked themselves in the mirror and wondered what they could do differently, while others have denied responsibility for people’s suffering, both physical and financial.

“We talk about celebrity a lot, which is tied to people’s positive emotional reactions,” Pollock said. “But there’s another kind of emotional reaction called infamy, which is a bad reputation associated with people’s negative emotional reactions that are highly visible.

“A lot of these industries have become infamous, and as the face of the companies, the CEOs will take the brunt of people’s ire.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

How CEOs Can Help Fix U.S. Health Insurance

By Daniel Butcher

In the aftermath of the killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson and the arrest of suspect Luigi Mangione in December 2024, it’s crystal clear that many people are deeply dissatisfied with the U.S. health insurance industry. With no realistic hope for legislative reform on the horizon, though, the onus is on employers to ease the administrative burden on employees and go to bat for them when health insurers or third-party administrators (TPAs) deny coverage of their doctor-recommended procedures, medications, and other medical services.

Academy of Management Scholar Tim Pollock of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville said that whenever he’s spoken to people who work in human resources (HR) about this issue, they often say that they don’t have sufficient staff members to handle benefits-administration oversight. In that case, it’s up to C-suite executives to come up with a solution for proper oversight of insurers and TPAs.

“HR people often say that’s the responsibility of the insurance companies, and many organizations outsource benefits administration,” Pollock said.

“Part of what they should be doing, though, is tracking this stuff and saying, ‘Okay, are we getting what we’re paying for?’ because things like health-insurance costs and benefits are hugely important to their employees, but they’re treated as a fringe benefit by the company,” he said.

“It isn’t a primary focus for CEOs—they don’t consider it to be part of what they need to be doing, but that would be a great thing for them to do.”

A coordinated effort to prioritize oversight of health insurance and benefits administration among senior executives at U.S. companies could help employees’ well-being and healthcare outcomes.

“Even a Walmart or some other company that employs millions of people, they’re one company in the face of a huge [healthcare] industry, but if you had a bunch of CEOs of big companies band together and say, ‘This is not adequate. This is not sufficient. We aren’t happy with the services that we’re being provided,’ and they make it public, that could bring about change,” Pollock said.

“Going public has to be a big part of it; that’s going to help bring pressure to bear on health insurers and TPAs, because one of the challenges they face is the U.S. insurance company playbook as well, which says, ‘Okay, fine, then go work with somebody else,’” he said.

“But they’re all doing the same stuff, so employers don’t really have an alternative, and it’s to the extent that either somebody can come along and provide a different kind of service, which is going to be very hard, or employers are going to have to try to find ways to put pressure on insurers and TPAs collectively, publicly, building on the emotional reaction that people in the U.S. have had to high healthcare costs, administrative burdens, and frequent denials of medical services.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

Three Types of Pay Transparency Are Changing the Game

By Daniel Butcher

While there isn’t a nationwide pay-transparency law in the United States—at least not yet—10 states, several cities, and even one county (Westchester, New York) have such regulations. That means organizations may need to adjust how they communicate about pay depending on where they’re based and where they operate.

Academy of Management Scholar Peter Bamberger of Tel Aviv University said one type of transparency is letting employees freely talk about their pay with one another. That’s been protected by U.S. federal law since the passage of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) in 1935.

“Most employees don’t know that they have the right to talk about their pay with other employees—that’s part of the NLRA. Still, companies discourage it, and in fact, some companies go too far in discouraging it so that they’re actually breaking the law,” Bamberger said.

“There’s very little merit to stopping employee disclosure, particularly since we now have things like Glassdoor, which really make it easy for employees to find out what others are earning in return for disclosing their own compensation,” he said.

In the second type of pay transparency, employers disclose compensation ranges to current and prospective employees.

“Laws in more than a dozen U.S. states and several cities are pushing for some degree of partial transparency with mandatory employer disclosure of pay ranges,” Bamberger said.“Going beyond that, where it’s not ranges that employers show, but rather actual individual rates of pay, can be potentially risky.

“Our studies have found that letting employees see how much coworkers make tends to have some pretty detrimental effects, whether it comes to malicious envy or even counterproductive work behavior,” he said. “The comp ranges not so much, but revealing detail about how much specific individuals are making can be problematic, so you have to be very careful about how you go about doing it.

“There are some success stories that I’ve written about in a book that I wrote about pay transparency, but it can be problematic.”

The third type is procedural pay transparency, from which Bamberger and his research colleagues have found only positive outcomes.

“That is being open and transparent about every aspect of the pay system in your organization, telling employees about the basis of the compensation structure, for example, what are the criteria for increasing bonuses? How were bonuses calculated this past year? How are differential pay rates by levels in the organization determined?” Bamberger said.

“Most employees don’t have a clue as to what their benefits are or how compensation levels are determined in the organization—employee pay knowledge is really minimal,” he said.

“Where organizations enhance this procedural pay transparency, perceptions of justice and fairness increased dramatically, and that has a wide range of beneficial effects and implications on retention, social exchange and reciprocity among coworkers, and giving back to the organization.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

Why You Should Be Kind to Medical Staff

By Daniel Butcher

While many people worldwide experience frustration with their healthcare system, taking it out on individual healthcare workers can backfire. Rudeness toward medical staff can lead to more delays and even errors.

Academy of Management Scholar Peter Bamberger of Tel Aviv University said that being rude to doctors, nurses, and other medical staff can hurt their job performance because it consumes valuable cognitive resources. In short, rudeness creates a huge mental distraction.

“Our theory was that when you experience rudeness, you’re distracted because of it, and you’re not even aware that you’re distracted. But you are distracted, and as a result, you can’t pick up on a lot of the social signals that are being communicated by other people, and interactions with bosses, team members, and clients or patients are harmed by that,” Bamberger said. “We actually demonstrated that in a field experiment using medical simulations; we brought in doctors to a medical simulation center where they were working on mannequins.

“Simulation centers are increasingly used to train doctors; they have all the equipment there: They can intubate, they can see X-rays, they kind diagnose and treat maladies,” he said. “So we look at the way they interact with each other; how do they try and transmit information to each other? How do they share tasks?”

Bamberger and colleagues recorded the medical team processes while working at the medical simulation center.

“We look at their diagnostic performance, their treatment performance, and their general patient management in an intensive-care context,” Bamberger said. “First of all, what we find is that individuals who are experiencing rudeness have significantly poorer performance than those who don’t.

“It’s interesting that this rudeness experience at the start of the day has lingering effects throughout the day; it doesn’t just go away after an hour or two,” he said. “The poor diagnostic and treatment performance stays on throughout each of the scenarios that they have to deal with over the course of the day, even after lunch, so they just come in at eight in the morning, they finish at four in the afternoon, and this stuff—being distracted by bosses’ or patients’ rude behavior while they are unconsciously trying to assess any possible threat—goes on all through the afternoon.

“The differences in staff performance pre- and post-rudeness are clear.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts