By Daniel Butcher

Whether people increase or decrease the amount of alcohol they drink after retirement depends on a range of factors, including what role and industry they retire from.

Academy of Management Scholar Peter Bamberger of Tel Aviv University said that he and colleagues studied the implications of general work-related transitions on health and well-being, with a particular focus on subjects’ behavior with regard to drinking alcohol, before and after retirement.

“We actually started with people as they move towards retirement, and we did a 10-year study,” Bamberger said. “The research was finding mixed effects of retirement on alcohol consumption; some studies found that retirement is a great way to address your drinking problems, because you’re often removing people from a high-risk environment where people around them drink a lot.

“But other studies were finding that people go into retirement and move into a retirement community and happy hour starts at noon,” he said.

Bamberger’s and colleagues’ question was, ‘Is retirement good or bad with regard to alcohol consumption or misuse?’ They were looking at various factors that determine when a person’s level of drinking goes in one direction and when it goes in the other direction.

“A simple finding is, if you’re coming out of a high-risk occupation, for example, iron workers, people who build skyscrapers—this is an occupation that has its roots with very heavy drinking communities, so if you joined that occupation, at least in the past, you were likely to adopt those patterns, or you wouldn’t stay in the occupation,” Bamberger said. “So retiring from that is obviously going to be beneficial, because you’re taking yourself out of a social context of high alcohol consumption.”

But there are other variables to consider, including relationships with friends, family, and spouses. A best practice for retirees is keeping busy with hobbies, volunteerism, or even some part-time work, any activity aimed at staying engaged and connected and ensuring a continuing sense of self-worth and contribution.

“We looked at some of the factors that are associated with retirement, like financial stress and marital strain, with one member of a couple working the other one not, and we can find implications there as well for drinking,” Bamberger said. “The routine is disrupted; there’s more free time for one partner in the relationship but not the other.

“There’s a vast array of moderating and conditioning factors that determine when retirement has one implication—more drinking—versus another—less drinking,” he said. “Retirees who plan how to structure their time post-separation from work tend to have better health outcomes.

“Overall, work-related transitions can be difficult for people, and our current research has aimed at exploring the mental-health implications of other such transitions, including for students and soldiers transitioning into career employment for the first time.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

When Entrepreneurs Can’t Acknowledge Failure, Disaster Strikes

By Daniel Butcher

Elizabeth Holmes, who was convicted of fraud for lying about the effectiveness of the blood-testing product of her biotechnology company, Theranos, is a cautionary tale illustrating a potential downside of entrepreneurship. Unable to deal with the failure of her company’s blood-testing methods, she just plowed ahead, refusing to acknowledge the disappointing results or telling any of the investors—or anyone else—that the tests weren’t working. She pretended like everything was okay, continued to collect investor money, and built up the biotech startup to a $9 billion valuation.

Academy of Management Scholar Dean Shepherd of the University of Notre Dame said that it’s common for entrepreneurs to deal with failure poorly, but investors failed to effectively scrutinize Theranos.

“A lot of the stakeholders there were maybe willfully ignorant—they wanted to believe her,” Shepherd said. “They didn’t ask probing questions; they ignored the negative signals, which is what we call a confirmation device.

“They look for information that confirms their opinions, and they discount or ignore information that disconfirms them, and so in many ways, she was negligent, but they were also negligent,” he said.

Sometimes entrepreneurs can’t even acknowledge failure to themselves, much less publicly, because their entire identity is wrapped up in success. One major failure could crack that self-image.

Shepherd said that job loss—or the failure of one’s business—can devastate a person’s sense of identity. He wrote about his research findings related to such phenomena in Hitting Rock Bottom After Job Loss: Bouncing Back to Create a New Positive Work Identity.

“Failure can have a huge impact on you psychologically, because your identity is quite often highly related to the things that you do for work, and when you lose that identity, you go into a crisis or a freefall, because you don’t know who you are anymore,” Shepherd said. “And if you don’t know who you are, you don’t know how to socially act, and it can be a very dangerous situation.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

Entrepreneurs Face Several Dangers

By Daniel Butcher

While entrepreneurs’ success stories get most of the publicity, the dangers they face are rarely talked-about elements of entrepreneurship.

Academy of Management Scholar Dean Shepherd of the University of Notre Dame noted that professors, business-book authors, and other journalists often tout the benefits of entrepreneurship without talking about its downside: Entrepreneurs often struggle and fail, sometimes with bad consequences for themselves, their colleagues, their loved ones, and even society.

“For quite a while, I’ve been researching entrepreneurs losing their business and people working on projects at an entrepreneurial firm when those projects fail,” Shepherd said. “The dark side of entrepreneurship is the negative emotional and psychological costs.

“The downside of entrepreneurship is the loss of your capital, your money, your personal finances,” he said. “And then there’s the destructive side—we always assume that entrepreneurship is doing good for other people, but it may not be.

“There might be some people who are greedy and engage in entrepreneurship that has a net destruction of wealth, so that really actually harms the natural environment or harms other people in order to just benefit themselves, or they didn’t mean to do it, but it just worked out that way.”

Opportunities exist in environments of uncertainty, so failure is going to be part of entrepreneurial endeavors. Entrepreneurs—and the people writing about them—should ask: What about the downside risk?

“Everyone says entrepreneurship is so good, and I do love entrepreneurship, but if we don’t understand the dark side, then how do we help entrepreneurs overcome some of the challenges they face being an entrepreneur, particularly when entrepreneurs pursue opportunities,” Shepherd said.

“We have to be able to help entrepreneurs minimize the potential losses from their action and avoid destructive entrepreneurship,” he said. “If we don’t understand why and how some people destroy societal wealth or the environment, then how are we going to be able to stop them?”

Shepherd highlighted a key question: “How are we going to be able to educate entrepreneurs to make sure that they don’t do that, and that they’re productive, rather than destructive?”

“The whole stream of my research along those lines is to try and really understand the flip side of the coin, because if you don’t understand the flip side, then you don’t understand the coin completely,” he said.

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

Dealing with a Failed Business

By Daniel Butcher

Most people’s reaction to the failure of their own business going under is like grief after the loss of a loved one. For many entrepreneurs, the best way to cope with failure is switching between talking about it and reflecting on it, according to Academy of Management Scholar Dean Shepherd of the University of Notre Dame.

Shepherd said that for some people, the more they talk about it, the worse their emotional reaction to the painful event gets. But for others, talking about their business failing can be cathartic.

“For some people, talking about failure helps them process it, but for others, dwelling on it causes the negative emotions to worsen, and that people actually need to have some periods where they can recharge their emotional batteries,” Shepherd said.

“The most recent research in that area said people actually have to oscillate between these two, a loss orientation, where you’re focusing on it, and a restoration orientation, where you’re deliberately ignoring it, not thinking about it, and start addressing secondary causes of stress, like selling the house, moving the kids from one school to another, these types of things,” he said.

“The important part is oscillating between the two, which I thought this was the weirdest thing, but I wrote a paper that ended up getting accepted in the Academy of Management Review, and then that set off quite a stream of related research.”

Shepherd then asked himself, “What happens if the organization doesn’t disappear, but the project that I’m working on does?” He worked on a paper with two coauthors about the negative emotional reactions that scientists working in Germany have when their projects fail.

“Those who are able to learn the most from the failure and those who were motivated to try again were the ones who were engaged in this oscillation process—they used both loss orientation and also restoration orientation,” Shepherd said. “They were able to learn the most and remain committed to the organization.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

The Secrets to Success for “Metacognitive” Entrepreneurs

By Daniel Butcher

Despite being dyslexic, Richard Branson co-founded Virgin Group in 1970 and eventually became a billionaire, British knight, and celebrity. He has speculated that his dyslexia was actually an asset by forcing him to think in less conventional ways when brainstorming, as well as launching and running businesses.

Academy of Management Scholar Dean Shepherd of the University of Notre Dame said that research by him and his colleagues shows that more “metacognitive” entrepreneurs are, the more adaptable they are and the more likely they are to pivot, ultimately achieving better results. Metacognition is about understanding how your own brain makes sense of the world, how your learn, and how you solve problems.

“Branson, who founded the Virgin Group, has dyslexia, and in an interview he was saying it was because of that dyslexia that he had to learn how to think in a different, more deliberative way, rather than rely on intuition,” Shepherd said. “He attributes his success as an entrepreneur to his dyslexia, because he engages in metacognition, thinking about the way that we think about things—we often just make decisions based on intuition.

“We don’t think about things; we just make an automatic decision, and sometimes our intuition is right, but sometimes it can be wrong, and if we’re not thinking about it, we don’t question it,” he said. “And with dyslexia, he learned these learning skills, which made him more metacognitive, so he thought more about the way that he thinks about things.”

Research on primary schools found that children who are taught metacognitive skills perform significantly better in reading and mathematics. Those metacognitive skills can be applied to entrepreneurship and leadership as well.

“Rather than just assuming that they’ll figure it out intuitively, practitioners of metacognition ask themselves four questions: ‘What is the problem really asking? What are we really facing here? How is this similar to something that we’ve faced in the past? And how is it different from what we’ve faced in the past?’” Shepherd said. “It stops us from doing this automatic thinking, then we say, ‘What’s the best way to approach this problem? What are the different ways that we can approach this situation?’ and choose one.

“As we’re engaged in that, we stop ourselves to reflect and we say, ‘How am I doing? Am I heading in the right direction?’” he said. “When you use metacognition, you interrupt your intuition at different periods just to remind yourself to be a little bit more deliberative in the way that you think now.”

Intuition is important, Shepherd stressed. It’s an effective way to make quick decisions that is especially effective when it’s based on expertise. But problems arise for those who never question that intuitive decision-making process.

“There are some people who rarely question those assumptions based on intuition, but as we engage in metacognition, we start to question them,” Shepherd said. “And when you have dyslexia, it forces you to have that sort of thinking discipline in order to be more deliberative in the way that you think.

“That’s my that was my interpretation of Branson’s statement,” he said. “While I’m not sure if he would necessarily agree with all of that, he did say that it forced him to be more disciplined in the way he thinks.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

Election Loss Lessons for Democrats

By Daniel Butcher

Leading up to the 2024 U.S. election, Democratic candidates needed to do a better job of keeping their fingers on the pulse of American voters and taking their concerns about jobs and the high cost of living seriously, rather than insisting on painting a rosy picture of the economy, according to Academy of Management Scholar Tim Pollock of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Pollock noted a disconnect between Democratic politicians’ messages and what swing voters wanted to hear.

“People are saying, ‘I’m upset about this. This is what I see in my daily life,’ and Democrats talked at a more general, abstract level, saying, ‘It’s really not that bad because of this, that, and the other thing,’ and voters think, ‘Yeah, that’s nice, but that’s not my reality,’” Pollock said. “And so if you really want to influence somebody, especially when they’re having a really strong, visceral, negative emotional response, you have to try to understand where they’re coming from, acknowledge their pain, and talk about where they’re at.

“Even if you can’t come up with a perfect solution or what you’re proposing isn’t going to really be feasible, people are going to feel better if they think they’re acknowledged and recognized,” he said. “That’s similar to what we founding the research studywe did about social-media influencers, who are effective at talking about people, saying ‘you’ not ‘me,’using language that conveys an understanding of where their audience is coming from, and talking to them about their issues—that’s what people want.

“They want to they want to feel seen and heard.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

Media Magnify Scandals of Big-Name Companies

By Daniel Butcher

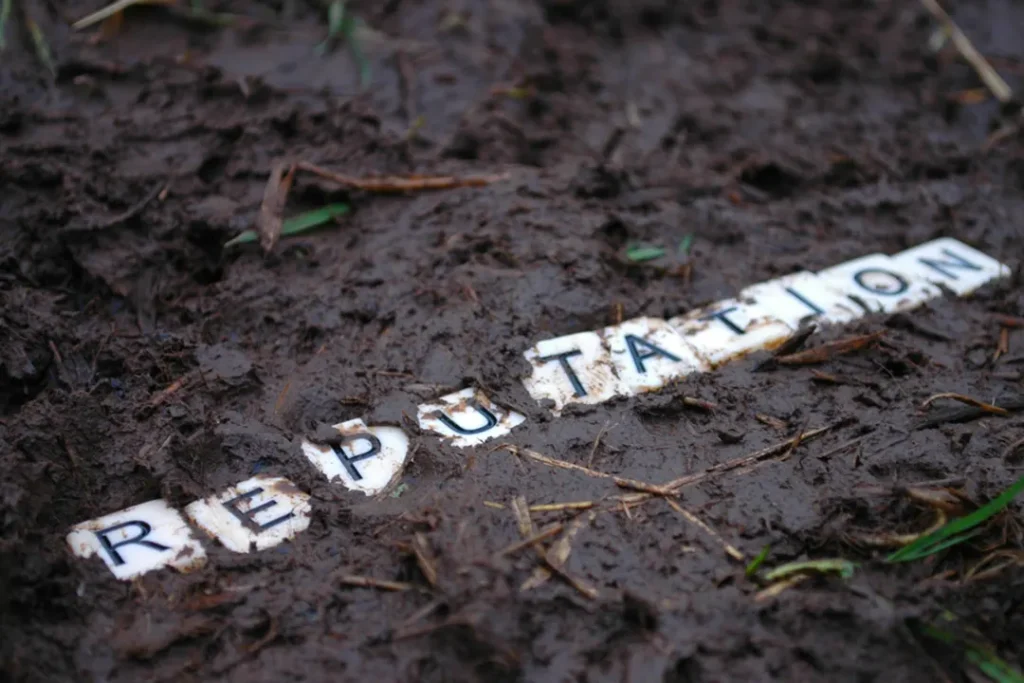

Companies that dominate their industries also have to deal with increased scrutiny. Any negative news, from layoffs and unethical conduct to data breaches, get amplified and can easily become scandals, according to Academy of Management Scholar Tim Pollock of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Media attention is drawn by the accused or guilty party’s prestige, he said.

“If the perpetrator is high-reputation, they may get the benefit of the doubt for less severe misconduct as some kind of one-off thing, and the media may be less likely to cover it,” Pollock said. “But if the misconduct is severe, then the media is even more likely to scandalize the high-reputation firm’s misconduct, because we don’t expect that from high-reputation firms; it violates our expectations.

“When we have high expectations about a firm’s behavior, whether because we expect them to be more competent or act with more integrity, it’s a bigger deal and more disturbing when they violate that expectation,” he said. “That makes the incident more newsworthy to the media, increasing their coverage of the misconduct.

“These are sorts of things that we’re looking at and trying to understand: What are misconduct aspects and firm characteristics lead the misconduct to become a scandal?”

Pollock and colleagues compared the reactions to data breaches at two different companies of vastly different levels of prestige and name recognition: Facebook and Chegg, a U.S. education technology company that provides homework help, textbooks, online tutoring, and other student services.

“Facebook had a data breach of 50 million accounts; it was covered widely in the media and got lots of attention—thousands of articles were written about their data breach and the problems with it,” Pollock said. “And literally on the same day, Chegg, which is an academic software company, had a similar data breach—40 million accounts were breached, but it was barely covered outside of the the specialist media on data security, and a little bit in the in the education sector.

“So why Facebook and not Chegg? Facebook is better known,” he said. “More people use Facebook and have given them their data, so the expectancy violation is greater and possibly more personal.

“Journalists recognize this, and thus are more likely to scandalize the incident, because it attracts more readers.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

The Disconnect Between Leaders and Patients on Healthcare

By Daniel Butcher

Many people hurt by the high costs and insurance denials plaguing the U.S. healthcare industry might have been hoping that the response to the December 2024 killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson would lead to reforms. However, most industry executives have tried to go back to business as usual, except with heightened security for senior executives, according to Academy of Management Scholar Tim Pollock of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

In response to the waves of criticism directed at U.S. health insurance and benefits-administration executives in the wake of Thompson’s killing, most industry leaders followed a typical crisis-management playbook, including a predictable public-relations script, he said.

“They’ve been saying all the things that they always say: that they’re beholden to achieving financial goals and medical providers’ increasing costs—‘medical costs go up, and so the insurance premiums have to go up’—and that they’re doing their best to provide coverage, and all these sorts of things, the usual platitudes that they roll out,” Pollock said. “But in terms of actually making some substantive changes, they don’t do much.”

“We’re one of the only countries in the world where healthcare coverage is privatized, and we’ve got the most expensive healthcare in the world with the 44th-best health outcomes,” he said. “It’s hard to justify the status quo on any rational basis.

“So if they want to repair and protect their reputation with customers and avoid this kind of backlash in the future, they have to understand where the customer is coming from and then find ways to speak to those problems and offer up a set of policies or practices they’re going to engage in—changes they’re going to make—to make this easier and better for customers.”

Health industry executives who try to defend the status quo of the U.S. healthcare system come off as tone-deaf at best, and uncaring or willfully dismissive of people’s suffering at worst.

“One of the mistakes that a lot of CEOs make is they try to defend the status quo, instead of saying, ‘You’re right; we’re not doing what we should be doing,’ and then, ‘Here’s what we’re going to do to make it to make it better,’” Pollock said. “There’s a whole other set of issues related to whether or not these things get implemented, but at least symbolically acknowledging their pain, their anger, taking some responsibility for it, and then saying, ‘We’re going to make changes that will address these problems and make things better going forward’ counts for something.

“But if they come out and talk about profitability, that their responsibility is to shareholders, or that this isn’t really a problem, or try to downplay the challenges that people have with high costs, denials of coverage, and administrative burdens, there’s a disconnect from patients’ experiences,” he said. “This is the issue you run into when leaders and customers are coming at a problem from opposite sides or completely different perspectives.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

How Fitness Influencers Gain Social-Media Engagement

By Daniel Butcher

Fitness influencers use various tactics to build their personal brands, attract followers, and inspire engagement on social media that can be applied to any topic or community.

Academy of Management Scholar Tim Pollock of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville said that people trying to build their follower base on social-media channels need to be proactive.

“You want to post a lot and comment on others’ posts and pictures, but also put out your own pictures on Instagram or the platform of your choice that people can engage with and relate to,” Pollock said. “Looking at fitness influencers, we saw before-and-after pictures of either the influencers themselves or their clients, somebody who was heavier or not that muscular before and now here’s a picture of them and they’ve lost 50 pounds and now they’re ripped, that kind of thing.

“Or here’s a selfie; here’s a picture of the influencer doing some kind of really cool exercise,” he said. “And usually they try to do them in some sort of funky location too, so it’s not just in the gym, but they’ll be doing them on the beach or in the mountains, and those sorts of things enhance engagement.”

Pollock said that influencers who share details about their personal lives are viewed as more authentic and likeable.

“Personal stuff is something that that makes me want to know a bit more about you and allows me to connect with you as a person,” Pollock said. “These were called ‘warmth images,’ things like you in a group with other people doing social activities, pictures of you with your family or kids, these kinds of things that gave some insight into who you are as a person.

“Beyond just the fitness pics, influencers also attracted people and pulled them in with personal posts and warmth images,” he said. “And then, using positive emotional language and talking about the other person and congratulating them were ways that fitness influencers enhanced the engagement with their posts.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

Why Many Leaders Ignore Criticism

By Daniel Butcher

In the wake of the U.S. public’s reaction to the killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson and the arrest of suspect Luigi Mangione, some CEOs in the health insurance industry downplayed the tragedy, rather than thinking about the root cause of people’s anger directed toward them.

Keeping blinders on is a red flag for narcissism, according to Academy of Management Scholar Tim Pollock of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. He and Arijit Chatterjee of ESSEC Business School researched narcissistic CEOs and found that the more narcissistic the executives are, the more likely they are to ignore critical messages, and surround themselves with yes-men.

“Many CEOs, especially narcissistic ones, surround themselves with people who say, ‘No, don’t listen to the critics. You’re great. You’ve done nothing wrong. Everything’s wonderful,’ as opposed to saying, ‘Hey, we’ve got a real problem that we need to fundamentally think through and deal with,” Pollock said. “So there’s nobody to rein in CEOs when they’re making bad decisions or alert them to a blind spot that they have.

“We all have good ideas and bad ideas, but leaders need people to tell them when they have a bad idea and to stop them from from acting on it,” he said. “When you don’t have those people in place telling the CEO to tap the brakes, the bad ideas just spread, and a narcissistic CEO doesn’t want to hear the negative stuff, whereas a less narcissistic CEO who really wants todo the best job possible will actually cultivate that and make sure they have people around them who will tell them the truth, even if it’s something that they don’t really want to hear, but that they need to hear.

“But a narcissistic CEO will fire truthsayers; they’ll get rid of people who they perceive as disloyal for telling them negative stuff or telling them that they’re wrong.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts

Up next....

Reactions to CEO’s Killing Illustrate U.S. Health Insurers’ Bad Rep

By Daniel Butcher

The killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson in New York in December 2024 exposed Americans’ intense frustration and deep-seated anger at the U.S. healthcare system. They’re forced to pay more and more for health insurance every year, while dealing with administrative burdens and denials of doctor-recommended procedures, medications, and other medical services.

Academy of Management Scholar Tim Pollock of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville said that people’s reactions to Thompson’s killing point to the horrible reputation that the U.S. health insurance industry has with the general public.

“Almost anyone in the U.S. you talk to about health insurance has complaints—I’m sure you could probably recount your own healthcare or health insurance war story, when something got declined, or you had problems getting treatment or getting [a procedure or medication] paid for,” Pollock said. “It happens to everybody in the U.S., and in some cases it can be pretty devastating, resulting in bankruptcy and losing all your assets when you have to absorb the costs when coverage is denied for a medical emergency or an expensive medical treatment.

“So there’s a lot of anger around how our healthcare system has been working or failing to work for for people, and it creates this pent-up anger in the [American] populace,” he said. “And so, aside from leading one person who was clearly having additional issues to go out and kill the CEO of UnitedHealthcare, you see the public respond by putting up these social-media posts, like ‘Request for thoughts and prayers denied’ and ‘You failed to get prior approval for having an object removed from your chest, so therefore, it will not be covered’—that kind of stuff, and making the shooter almost a folk hero in certain quarters.

“These kinds of posts that people are putting out there and many others cheering them on speaks to the anger that folks have.”

Merriam-Webster defines infamy as an “evil reputation brought about by something grossly criminal, shocking, or brutal.” Some health insurance leaders have looked themselves in the mirror and wondered what they could do differently, while others have denied responsibility for people’s suffering, both physical and financial.

“We talk about celebrity a lot, which is tied to people’s positive emotional reactions,” Pollock said. “But there’s another kind of emotional reaction called infamy, which is a bad reputation associated with people’s negative emotional reactions that are highly visible.

“A lot of these industries have become infamous, and as the face of the companies, the CEOs will take the brunt of people’s ire.”

-

Daniel Butcher is a writer and the Managing Editor of AOM Today at the Academy of Management (AOM). Previously, he was a writer and the Finance Editor for Strategic Finance magazine and Management Accounting Quarterly, a scholarly journal, at the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). Prior to that, he worked as a writer/editor at The Financial Times, including daily FT sister publications Ignites and FundFire, Crain Communications’s InvestmentNews and Crain’s Wealth, eFinancialCareers, and Arizent’s Financial Planning, Re:Invent|Wealth, On Wall Street, Bank Investment Consultant, and Money Management Executive. He earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and his master’s degree from New York University. You can reach him at dbutcher@aom.org or via LinkedIn.

View all posts